There are many important things that can help a poet continue to write poetry at any age, but encouragement and opportunity come top of the list.

As a teenager often a typical school environment in the UK can seem hostile to anyone whose interests are a little different. I was often seen at school as a little dreamy or too verbose and whilst children can be unkind to one another, amazingly, teachers can also misjudge their own reactions to pupils that don’t fit nicely into the system. They can get caught in the exam grade trap where anything above and beyond what is required to get the school a good set of results is pushed aside.

In my mid-teens discovering the excitement of words and how they can give greatly nuanced meaning fascinated me and I wanted to use them in my essays. My English Literature teacher at the time disagreed and I was made an example of for using words that were too long or that people might not understand. Rather than encouraging word and language experimentation in a young person by setting a separate project, she made it clear that anything beyond the basic remit would be frowned upon.

For me though, I was lucky, there was one other person who became my ally during those difficult school years. I would often visit the empty school library to talk with a softly spoken woman called Miss Munro. She told me my poetry was wonderful, she published my work in the school magazine and gave me encouragement to keep writing when the darker clouds of self-doubt and despair at my ‘outsider’ qualities led me to her door. When I was 14 she entered one of my poems into a competition to appear in an International anthology, something that I would never have thought to do, something that gave a boost to see my work within the pages of a real book.

After leaving school the material world hit hard. Friends talked of making money in ‘serious’ jobs and passed opinion about poetry as something that did not fit into that category. I learnt that, out in the ‘real’ world, the very thing that made life worth living for me at that age was perceived as something that could not hold any worth unless some form of monetary security was attached. The trouble with writing poetry is that often it isn’t something you suddenly decide that you will start to do or refrain from- it is just part of you.

Many times I had wanted to contact Miss Munro again for the reassurance that poetry was still ‘the’ thing that mattered, but instead always decided against it for one reason or another . And so, like Miss Munro and Larkin who became librarians to support their poetry, I decided to become a journalist to allow me to write. It has been a struggle over the years, as a lot of poets will know, when the pace of their daytime job, strange illnesses, car accidents, deaths and births flood in to drown out and swallow up the poet inside.

More recently I thought I would finally contact Miss Munro again and began a search for her home address. I was amazed to find that Madeline Munro had been a gifted poet who had been ‘highly regarded among poets and writers, commended by J.M. Coetzee, D.M. Thomas, and others’. To me she had been a different person, the warm and friendly librarian who stacked books on the school shelves and who published my poems, such as they were at that time. The special person who had taken a great interest and encouraged me to continue to write and saved me from forgetting who I really was as a youngster.

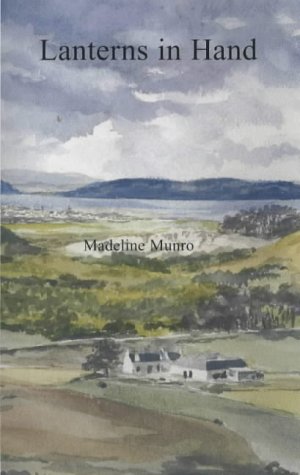

Unfortunately, I had left it too long and by the time I looked for her she was then into her 80s and had died. I will always regret that I never had the chance to tell her how much a part of the core of my early life she had been. I hope that by writing this article, more people will try and take a look at her work. It is difficult to locate Chant, as this early collection seems now to be out of print. However, many of the poems from this collection can be found in Lanterns in Hand and this can sometimes still be found. I have put a link to a few websites at the end of this article that look more closely at her work.

Madeline had won national prizes, published in magazines and produced a number of collections The Chant: A Highland Farm Childhood (1983), Lanterns in Hand (2003), Fe Fi Fo Fum: Poems to Fight Giants (1999) and White Rabbit with Yellow Flower and other animals (2008). J.M Coetzee said of her collection Lanterns in Hand: “I am impressed by the way in which a way of life that has now practically vanished, but which had its own unique enchantments, has been transmuted and saved by the hard craft of poetry”.

To have such praise from Coetzee and D.M. Thomas is testament to her poetic gift.

In her poem ‘The Chant’ she ends with the line: ‘What shall we chant now to lift the dark’ and whilst this line was written within the context of her own childhood memories it struck me how prophetic this single line is. How many times have we all looked for something that will take away our fear or the darkness. During the pandemic our collective ‘chant’ became poetry.

Although reading poetry has been on the rise for a while, a study (1)US Trends in Arts Attendance and Literary Reading: 2002-2017) revealed that in 2017 poetry reading surged by an incredible 76% in America and during the first year of the pandemic poetry became omnipresent in the UK. We suddenly had daily poetry readings on the ‘Today’ programme, it popped up everywhere on social media and our need for poetry was analysed in newspapers and web articles. Despite Boris Johnson’s government up-grading the sciences and down-playing the importance of the arts sector in society, the people had spoken. The reality being very different from Johnson’s made-up universe where ballerinas are forced to re-train in cybersecurity. The negative reaction from the public towards the government’s misguided advertising campaign was so great they had to pull the ad within weeks.

Poetry has the ability to connect with us, remove our fear or show solidarity, to make us feel a kind of release when someone else shares an emotion or transcends our own thought, lifts us to a place we want to be or shows us places we ought to understand. Poetry is borderless, in many ways it allows more scope than fiction, it needs no complex plot structure, it can reach out to us with just a few words.

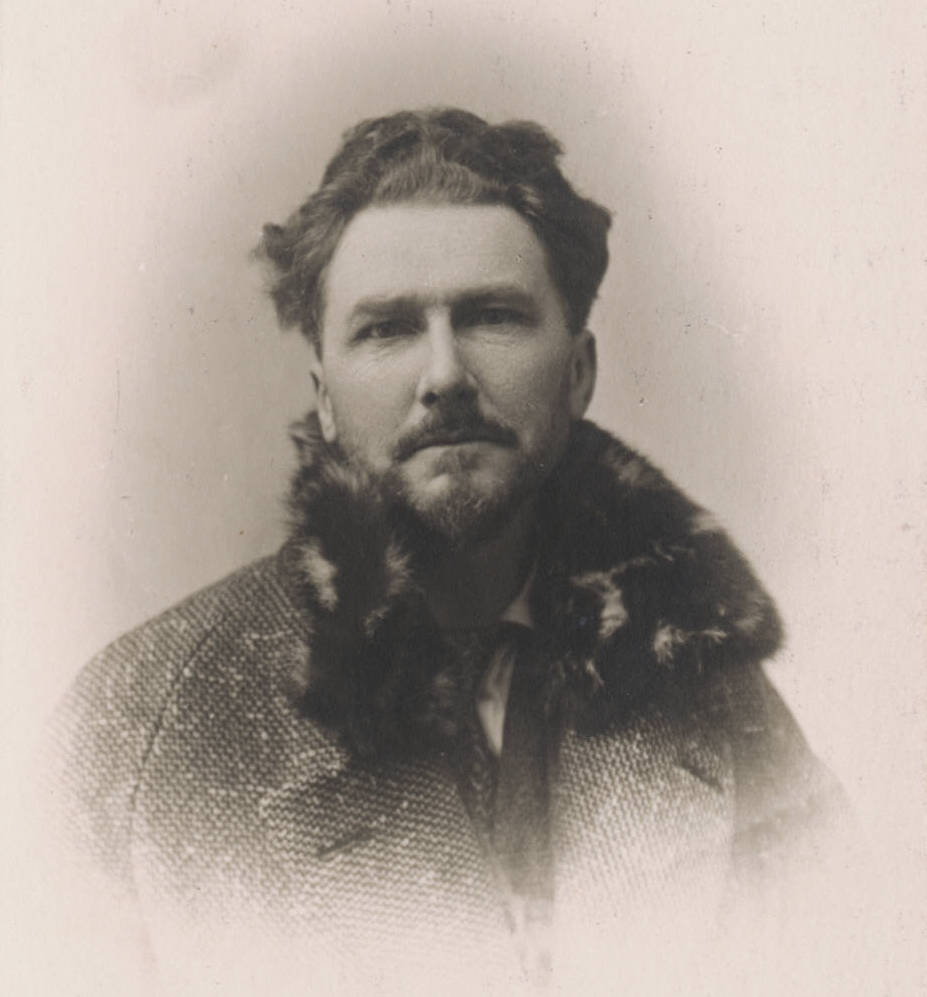

Out of all the poems written around the time of the present pandemic, for some strange reason, a poem that touched me more than any other had been written in 1913; a two line poem In a Station of the Metro by Ezra Pound. It had been published just five years before the last pandemic had struck during which Pound contracted the Spanish flu. I had known this poem for years but it kept floating back into my consciousness as a reminder of a simple beauty in humanity. When the streets became strangely empty of faces only a few people here and there, their eyes peeping above masks, I wanted to see again the crowds at the stations, the smiling faces, the look of lovers, contented mothers, friends, the tired and timid, strong and silent, kind or fearful, all expressing the beauty of human emotion.

The faces unmasked, going about their everyday business had suddenly struck Pound as particularly beautiful and he spent a long time trying to put into words exactly how these faces had appeared to him, finally concluding his vision had been as ‘petals on a wet, black bough’. Pound had managed to say so much in so few words.

The fourteen words read: The apparition of these faces in the crowd: Petals on a wet, black bough. And that is it. In and article that appeared in (2)The Fortnightly Review written by Pound a year after publication of the poem In a Station of the Metro, he explained how the poem came about. When Pound had got out of a metro train at La Concorde he had been struck by many beautiful faces. He had “suddenly seen a beautiful face, and then another and another, then a beautiful child’s face, and then another beautiful woman.” He sought to find words that were worthy of the emotion that had emerged in him on seeing the apparition of these beautiful people.

(Photo credit: Ezra Pound (Beinecka Rare Book and Manuscript Library via Wikimedia Commons)

Finally when some inspiration came to him it was more like an “equation” not in speech but “in little spotches of colour…the beginning, for me, of a language in colour.” He clarified this by adding: “I do not mean that I was unfamiliar with the kindergarten stories about colours being like tones in music. I think that sort of thing is nonsense. If you try to make notes permanently correspond with particular colours, it is like trying to narrow meanings to symbols.”

Over the next months Pound struggled to match his intensity of feeling for what he had seen and its realisation in words. Perhaps, he thought, his experience in Paris should have gone into a painting. He understood that if he had been a painter that he may have found a new school of painting that would “speak only by arrangements in colour”.

IN A STATION OF THE METRO

The apparition of these faces in the crowd :

Petals on a wet, black bough .

Ezra Pound(Above -Example of the word spacing as originally published in Poetry Magazine in 1913)

He grappled with the abstract concept of states of consciousness and how to convey them in word form for many months. Pound then wrote a thirty-line poem but destroyed it because he felt it conveyed only “second intensity” then six months later another attempt, this time a poem of fifteen lines or so and then a year later the final work, the now famous haiku-like description arose of his experience on the metro that day a year before.

In his article ‘Vorticism’ Pound tried to explain the final form of the metro poem. “In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective.” Whatever the ideology behind In a Station on the Metro, for me, the words work. They incite the emotion, a feeling of an abstract experience, and it was this I felt for the absence of those beautiful faces on our streets, and in all the cafes and metros.

The line from Munro’s poem Chant also gives me a sense of poetry crossing over the years into the future and this is the wonderful aspect of poetry, it is not static. It’s power lies in the fact that with just one line or fifteen words it can reach out into our heart our intellect and our sub-conscious.

Sources:

Lukemckernan.com

Press and Journal/TributesPaid-Highland Poet Dies age 86

USA Today/Reading fiction is down, reading poetry is up, says new study/Maria Puente

The Fortnightly Review/Vorticism/Ezra Pound (New Series)

The Guardian/Opinion/editorial/29.01/2021